It’s membership time. Cultivate Canada’s media. Support rabble.ca. Become a member.

“It’s one of the best businesses we’ve had in Quebec for decades.” – Montreal Mayor Gerald Tremblay, commenting on the “remarkable work” of construction magnate Antonio Accurso’s company at City Council on Tuesday. Accurso has been charged with fraud, conspiracy, influence-peddling, breach of trust and two counts of defrauding the government.

While news out of Quebec in recent months has focused on the student strike, and the social movement it has generated, that is not the only reason people here are dissatisfied with our government.

It has been common knowledge for years that our construction industry is riddled with corruption, and that political parties such as Premier Charest’s Quebec Liberal Party (PLQ) and Montreal Mayor Gerald Tremblay’s Union Montreal (UM) are deeply implicated in the rigging of bids and inflating of contracts in exchange for political contributions.

After stonewalling all attempts to launch an independent investigation into corruption in the construction industry and links to political parties for years, Premier Charest was finally forced to call such an inquiry earlier this year.

Commonly referred to as the Charbonneau Commission, after Justice France Charbonneau, its co-commissioner (along with Renaud Lachance), the Commission d’enquête sur l’octroi et la gestion des contrats publics dans l’industrie de la construction had been toiling away fairly quietly until this week.

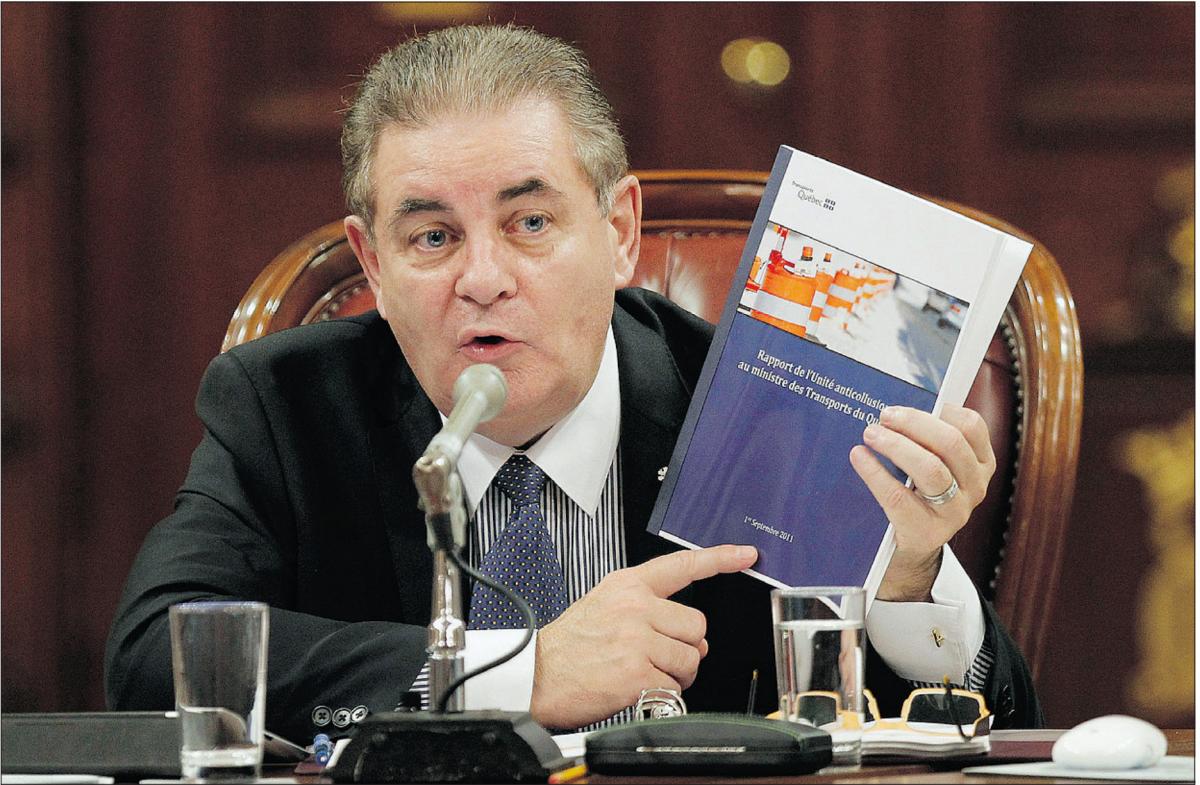

That’s when Jacques Duchesneau, former Montreal Police Chief, head of a special anti-collusion investigative unit and co-author of a damning report on corruption in the construction industry, took the stand.

In testimony this week he asserted that “dirty money finances elections”, arguing that a full 70% of political donations are made secretly, and illegally, without the knowledge of Elections Quebec.

Duchesneau’s first report, which he leaked to the press in the fall, detailed widespread corruption and collusion within Quebec’s Transport Department. Following its release he says he was approached by over a dozen people who provided him with detailed inside information on the financing of political parties.

Based on this information he took the initiative to prepare a second report, titled “Illegal financing of political parties: a hypocritical system where influence is for rent, where decisions are for sale”

Although this 50 page report was turned over to the Commission, it was not entered into evidence and as such is not publicly available.

In his testimony Duchesneau asserted that political parties have two pots, one for legitimate donations, and another for illegal contributions. The amount of illegal money flowing into party coffers is so large that party fundraisers “have had trouble shutting the safe’s door”.

He detailed a system in which party fundraisers approach companies for illegal contributions, and in exchange these companies will inflate invoices for work being done for the government. He said at least 50 companies in the Montreal area alone have submitted this type of “false” invoice.

In testimony this week, he and former employees Annie Trudel and Martin Morin did not shy away from naming names, although they refused to cite their anonymous sources, who they believe would be at risk of intimidation or violence if their identities were revealed.

They cited two companies, Neilson Inc. and EBC Inc., which had hired employees to scrutinize public contracts for loopholes which would allow them to add “extras” onto the work and overcharge the government.

Neilson is owned by prominent Quebec Liberal fundraiser Franco Fava, who was accused in 2009 of pressuring former Liberal Justice Minister Marc Bellemare to appoint his favoured judicial candidates to the provincial bench.

On Monday, Morin testifed that “Collusion is only limited by imagination, that’s what I have learned working on this.”

He, Trudel and Duchesneau took particular aim at companies owned by Paolo Catania and Antonio Accurso, two major construction magnates who have often been linked to corruption, and who were arrested and charged in a series of sweeps earlier this year by the permanent anti-corruption squad UPAC. Those raids netted over 20 people, including Mayor Tremblay’s former right hand man and chair of the city’s powerful Executive Committee, Frank Zampino.

All are charged with a wide variety of offences, including fraud, breach of trust, conspiracy, municipal corruption, breach of trust by a public official and being party to a criminal offence. Zampino has been accused by UPAC of being the “ringleader” of a bid rigging scheme which defrauded the city of up to 26 million dollars on one land deal alone. He has also been accused of providing insider information on bids to companies owned by Accurso and Catania, in exchange for lavish vacations, other personal perks and massive donations to the Mayor’s Union Montreal party.

But the corruption does not appear to be limited to Union Montreal. Former leader of Vision Montreal Benoît Labonté admitted back in 2009 to illegally taking $100,000 from Accurso to fund his leadership bid and alleged that many members of the provincial Liberal cabinet were closely connected with Accurso.

David Whissell, former provincial labour minister, was forced to resign from cabinet in 2009 over allegations of conflict of interest, when a paving company he co-owns received untendered contracts. His subsequent resignation from politics prompted the recent by-election in Argenteuil, where Liberals lost the seat for the first time in over 50 years.

Although we have had various parts of this puzzle for years, both Charest and Tremblay have insisted that the documented cases of corruption by senior members of their teams were isolated incidents.

The picture pained by Duchesneau and his colleagues this week is of municipal and provincial political parties where corruption is not the exception, but the rule. They outlined a political system driven by illegal contributions, where corruption is known about and encouraged at the highest levels.

Several Quebec mayors have already been arrested, as have many members of Montreal Mayor Tremblay’s inner circle, including his former right hand man Zampino and top fundraiser Bernard Trépanier. One has to wonder if charges will not be forthcoming against the Mayor himself, given the unlikelihood of his top people orchestrating such a complex system of corruption without his knowledge.

At this Tuesday’s Council meeting, Tremblay himself stood to argue that the city could not cancel pending contracts with Accurso’s company, because doing so would stall necessary repairs to municipal infrastructure. He defended the “remarkable work” of Accurso’s company, which he described as “one of the best businesses we’ve had in Quebec for decades”.

This to describe a company implicated in widespread corruption, bid rigging and fraud, which has been accused of defrauding the City of Montreal of 26 million dollars on one deal alone.

In 2009’s municipal election voters rewarded Tremblay with another term, despite widespread allegations of corruption. At the time retired justice John Gomery, who famously headed the Gomery Inquiry into the sponsorship scandal, took the unprecedented step of accusing both Union Montreal and Vision Montreal of corruption, and publicly backing Projet Montreal, which he described as the only “clean” party in municipal politics.

Projet did go from one seat to fourteen in that election, and is expected to be the main challenger to Tremblay’s Union party in elections next fall.

But how do you compete with the not-so-metaphorical suitcases stuffed with cash that Union will bring to the table?

And at the provincial level, where an election could come as early as this fall, what is the alternative? Duchesneau’s testimony did not cite political parties by name, although it is clear that he was referring to the governing party in Quebec and Montreal. But what about the opposition? We’ve known for years of ties between Vision Montreal and Accurso, and the implication that this illegal financing racket is a system which has been in place for years certainly casts doubt on the PQ, and their actions in government and fundraising since.

People like Accurso and Catania don’t back one horse, they back many, so that no matter who wins, their sweet deal remains in place.

The Coalition pour l’Avenir du Quebec (CAQ) are too new to have much public baggage, but since the party is led by former PQ cabinet minister Francois Legault, and made up of former Liberals and Pequistes, I don’t place a lot of stock in the idea they would do things any differently.

Quebec Solidaire has a reputation similar to that of Projet Montreal, of being incorruptible. But their chances of winning the next election outright are low. The truth is, we’re pretty screwed at the provincial level.

As Duchesneau said, this system is deeply entrenched in Quebec, at both the provincial and municipal level. “No matter what the rules, people will get around them. The only real deterrent is the certainty that you will be caught”.

To get that certainty, we need a provincial government dedicated to rooting out corruption, rather than covering it up. The Liberals are clearly the worst choice by a country mile, but I don’t have a lot of confidence in the PQ or CAQ either.

I think no matter what happens in the next provincial election we’ll be stuck with a lousy government. But every Quebec Solidaire MNA elected is one more voice which will call the government to account, and stand up for the interests of citizens, not corrupt corporate backers. That’s where my vote will go.

Meanwhile, we’re stuck with Charest’s gang, who argue that accessible education is an unaffordable luxury while shoveling taxpayer money out the back door to companies which in turn finance their election campaigns.

Stop the system, I want to get off.

Follow me on twitter @EthanCoxMTL

For more information on the Charbonneau Commission check out Monique Muise, who has been doing great work covering it for the Montreal Gazette. A lot of my research for this piece was based on her articles.